Key Points

Anal sacs are glands that produce territorial marking secretions which are expelled in small quantities with each bowel movement.

Anal sac adenocarcinomas can be identified via rectal palpation.

The treatment of choice for anal sac adenocarcinoma is complete surgical excision.

In general, dogs which have early, complete excision of the tumor are likely to have the best outcome.

Introduction

Anal sacs lie just inside the anus of most carnivorous species. They are paired structures (one sac on each side of the anus), which are lined by many glands. These glands produce secretions that are expelled in small quantities with each bowel movement as a form of territorial marking. In skunks the anal sacs are the scent glands which are released as a form of self-defense…we are all familiar with that smell.

Anal sac tumors arise from the glands of the anal sac, and may be benign (anal sac adenomas) or malignant (anal sac adenocarcinomas)—most anal sac tumors are of the malignant type. These anal sac adenocarcinomas make up approximately 2% of all skin tumors seen in dogs, and of these dogs, the majority are older females. There are no obvious breed predilections and this type of tumor occurs in both intact and neutered animals. Anal sac adenocarcinoma is very rare in cats, but has been reported.

The tumor itself is usually unilateral (affecting only one of the anal sacs), however bilateral tumors have been recognized, so both anal sacs should be carefully examined. The mass may be discrete or infiltrative, and can be very small (less than 1 cm in diameter) or quite large (up to 10 cm or more in diameter). It frequently produces a hormone which causes blood calcium levels to rise above normal levels. This is known as hypercalcemia of malignancy, and can cause problems with other organs such as the kidneys. In addition, anal sac adenocarcinomas have often metastasized (spread) by the time they are initially diagnosed. They may spread first to regional lymph nodes, such as the sublumbar lymph nodes, and later to the lumbar spine or more distant sites such as the liver, spleen, or lungs.

Clinical signs

Common clinical signs of affected animals include difficult or painful bowel movements, straining to have a bowel movement, ribbon-like stools, or swelling of the area around the anus. If hypercalcemia is present, other signs such as increased thirst, increased urination, decreased appetite, weight loss, vomiting, muscle weakness, and low heart rate may be noted. In the event that the tumor has spread to the sublumbar lymph nodes or lumbar spine, lower back pain or stilted gait may be present.

Diagnosis

If a tumor of the anal sac is palpated, complete blood count (CBC), serum chemistry profile, and urinalysis should be performed to identify possible hypercalcemia, evaluate systemic health, and help identify any other abnormalities. About 50% of these patients will have high blood calcium levels.

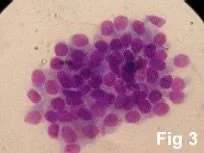

Aspiration of some cells from the tumor or sublumbar lymph nodes may be performed so that they can be examined under the microscope; fig 3 shows malignant cells from the tumor. CT scans have also been used when further testing needs to be pursued.

The definitive diagnosis of anal sac adenocarcinoma, however, must be made by surgically removing the tumor or by taking a biopsy of the tumor and sending in a sample for analysis of the tissue by a pathologist using a microscope (called histopathology).

Treatment options

Radiation therapy is another treatment option, which may be explored as adjuvant therapy. Cancer surgeons are seemingly going away from routine radiation of the anus, due to potential radiation-related side effects, but this treatment may be needed in some cases.

Potential complications

Even though rare, anesthetic death can occur. With the use of modern anesthetic protocols and extensive monitoring devices (blood pressure, EKG, pulse oxymetry, inspiratory and expiratory carbon dioxide levels, and respiration rate), the risk of problems with anesthesia is minimal.

Infection is also an unusual complication as strict sterile technique is used during the surgery and antibiotics are administered. A slight increase in the infection rate following anal sac carcinoma may be expected as this site is close to the anus (dirty).

Tumor-invaded lymph nodes are often closely associated with blood vessels, thus if sublumbar lymph nodes are removed there is a risk of bleeding during the procedure.

These lymph nodes are very close to nerves as well (especially those innervating the bladder), and removal may cause nerve damage leading to temporary or in some cases permanent post-operative urinary incontinence.

Fecal incontinence can follow surgery in a small percentage of animals.

Rectal prolapse can occur if the pet strains a lot and if the anal sphincter has poor function.

Anal stricture, an uncommon complication, will result difficulty passing stool.

Chronic fistula (a hole that develops between the rectum and skin around the anus) may develop if a portion of the rectum needs to be removed during the tumor removal surgery and the rectal incision fails to heal. This problem may require a temporary colostomy to divert feces from the area.

Postoperative evaluations

The tumor will be sent to a pathologist for analysis (histopathology). This allows a definitive diagnosis to be made, based on the cell types present in the tumor.

At this time, other forms of treatment such as chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy may be recommended.

Even if surgery is the only treatment advised, periodic reevaluation is very important to help ensure that the anal sac adenocarcinoma has not recurred or spread to other areas of the body. The following may be recommended:

Blood tests including calcium levels are often a good indicator of this, as levels will usually rise again if the tumor returns.

Rectal examination, Chest x-rays, Abdominal ultrasound

Prognosis

In general, dogs which have early, complete excision of the tumor are likely to have the best outcome. It is also important to note that many of these patients can be successfully managed, and continue to have a good quality of life for a number of years.

One report of five cases, in which only surgical excision of lymph node metastasis and the primary anal sac tumor resulted in a median survival time of 20.6 months. One dog had repeated removal of lymph nodes affected by metastasis and this dog survived 54 months.

Another series of 15 cases, the anal sac tumors were removed, however the metastatic lymph nodes were removed in only 4/7 cases. Radiation therapy was administered to the lymph nodes and mitoxantrone was administered (5 treatments). Median survival time was 31 months. Acute side effects of radiation were considered moderate to severe in 13/15 cases with signs of pain and perineal irritation being the most common. Four of 15 dogs had long-term straining during bowel movements due to radiation therapy.

In another study, which included 14 dogs with anal sac carcinoma, about 50% of these had metastasis to regional lymph nodes. In these cases, the anal sac tumor along with affected lymph nodes were removed and mephalan chemotherapy was administered. The median survival for dogs that had concurrent lymph node metastasis was 20 months and for the remaining dogs that had only the anal sac tumor (with no lymph node metastasis), the median survival time was 29.3 months.

The largest study, which included 113 dogs, showed that those treated with surgery and another treatment modality (radiation and/or chemotherapy) had a median survival time of 18.3 months versus 13.4 months with surgery alone. Dogs that had high level of calcium in the blood had a median survival time of 8.5 months versus dogs that had a normal blood calcium level had a median survival time of 19.5 months. Size also seems to matter: dogs with large tumors (>10 cm²) had shorter survival times.

References

- Hobson HP, et al. Surgery of metastatic anal sac adenocarcioma in five dogs. Vet Surgery 2006;35:267-270.

- Turek MM, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy and mitoxantrone or anal sac adenocarcinomas in the dog: 15 cases (1991-2001). Vet Comp Oncology 2003;1, 2:94-104.

- Anal sac tumours of the dog and their response to cytoreductive surgery and chemotherapy. Aust Vet J 2005 Jun;83(6):340-3.

- Williams LE, Gliatto JM, Dodge RK, et al. Carcinoma of the apocrine glands of the anal sac in dogs: 113 cases (1985-1995). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003 15;223(6):825-31.